[via Municipal Dreams]

A few weeks ago, Keeling House in Bethnal Green featured in BBC2’s Great Interior Design Challenge. Its presenter Tom Dyckhoff paid due homage to the building’s architecture – a Denys Lasdun brutalist masterpiece – and to its history. But let’s pay a little more attention to the latter here. Now privately owned, Keeling House was once a vision of high quality housing for the people.

Before the Second World War, Bethnal Green was the heart of the traditional working-class East End – with social conditions to match. At the height of the Great Depression, it was stated that 23 per cent of the borough’s men were unemployed and some 43 per cent of its population living in overcrowded conditions. (1)  Both the London County Council and Bethnal Green Metropolitan Borough Council built extensively to rehouse local people. The Claredale Estate was a local council scheme, begun in 1932.

Both the London County Council and Bethnal Green Metropolitan Borough Council built extensively to rehouse local people. The Claredale Estate was a local council scheme, begun in 1932.

Claredale House, facing Keeling House, was a solid red-brick and rendered 73-tenement block – designed by the architect ECP Monson, also responsible for the Borough’s earlier and notorious ‘Lenin Estate’ nearby. It cost £38,000 but, as Mrs Rawle, the chair of the Housing Committee, stated: (2)

The present and past borough councils did what they could to improve property and bring it to a better level. Their chief trouble was lack of money; in common with the other councils the Bethnal Green Council had not as much money for housing as it would like to have.

In a sign of the times, it’s now let by a housing association as single-room student accommodation. Back in 1945, there was added urgency to government’s mission to house the people – practically due to the impact of the Blitz, politically by the expectations raised by wartime promises. Much wider clearance and redevelopment followed.

The first contribution of Denys Lasdun to local housing came in 1952 when commissioned by the Borough Council to redevelop a bombsite off Usk Street. In Sulkin House – a small, eight-storey, two-wing block of 24 maisonettes, Lasdun pioneered the innovative ‘cluster block’ design that would mark out the larger Keeling House. (3) The key elements of this concept were the central, free-standing tower containing lifts and services and the separate towers containing accommodation which ‘clustered’ around it: (4)

The disposition of the plan is such as to eliminate the necessity of escape stairs and also isolates the noise of public stairs, lifts and refuse disposal from the dwellings.

It’s an ingenious design which breaks up the massed and repetitive appearance typical of normal tower or slab blocks. It allows more light and air into the building whilst simultaneously providing greater privacy and quiet to housing areas. Lasdun had thought this through carefully and his ideas owed much to his well-meaning if slightly patrician conversations with local residents: (5)

These were people who came from little terraced houses or something with backyards. I used to lunch with them and try and understand a bit more about what mattered to them, and they were proud people. They kept pigeons and rabbits in their back yard and hung their washing there…And as a result of these contacts I didn’t have flats. I said no, they must have maisonettes, two up and two down, or whatever it was, because this would give them the sense of home. And from these conversations, they wanted a degree of privacy. They said: you know, we’re not used to being in a great sort of huge block of one of thousands. So the thing was radically broken up, this building, into four discrete connected towers, each semi-d. on a floor, each a maisonette.

Keeling House writ the cluster block concept large. Completed in 1959, it was 16 storeys-high, four blocks around the central service core containing 64 homes in all – 56 two-storey maisonettes and, on the fifth floor and deliberately visible in the building’s profile, 8 single-storey studio flats. It’s an unashamedly brutalist design, constructed of reinforced concrete with precast cladding units of Portland stone finish.

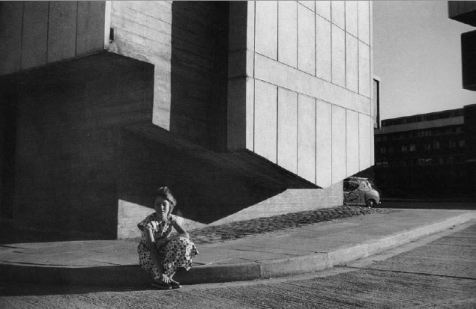

Ground level showing site-cast concrete and Portland stone, 1959

Photo Credit: RIBA Collections: click here to view original on RIBApix

It’s not to everyone’s taste. Locals reportedly found it stark and intrusive, out of keeping with the surrounding Victorian terraces. One resident of the block itself described it as ‘the ugliest building I have ever seen – ugly and bleak’. (6) But, to my eyes, Keeling House has a strength and cleanness of line and variety of surface and angle which is striking – it’s a building which takes the ‘brutal’ out of brutalism.

Perhaps views have changed more generally. And despite its scale, Lasdun tried carefully to preserve the best of the old whilst incorporating the benefits of the new. This was an attempt, it was said, to stand those Victorian terraced streets – dilapidated but vital – on their end.

The services areas of each floor were common – a place to dry clothes (before the era of tumble dryers) and meet and chat. Balconies, each serving only two flats, faced each other but did so obliquely, in a delicate balance of neighbourliness and seclusion. Three-quarters of the tenants could reach their front door without passing another. The housing blocks were angled to provide shelter to each other and each home was angled to receive sunlight at some point during the day. Each had a private balcony.

All – unlike their Victorian predecessors – enjoyed fresh air and views. The 800 sq ft maisonettes comprised a lower floor with spacious living room and kitchen plus a hall, pram store and box store. The upper floors comprised two double bedrooms, a bathroom and another, larger, box-store. This was not, despite the later jaundiced comment of a local councillor, a ‘monument to the stack-em-high principle of working-class housing’. (7)

Still, not all the high ideals worked out. What was good for drying clothes – the wind eddied around that central service area – did not make for leisurely conversation. Free access to the lifts, and thereby the common areas, left the block susceptible to problems – of vandalism and graffiti – which were common to many council estates in the 1970s and beyond. And structural problems emerged.

Tower Hamlets Council, Bethnal Green’s successor authority, spent £1.2m on repairs in 1984 –perhaps unwisely as we shall see – but within a few years things had got worse. Residents reported damp, cracks appeared in staircases and the concrete cladding started to crumble. In October 1991, a Dangerous Structure Notice was served on the block and, in the following year, as its deterioration accelerated, residents were required to vacate.

Tower Hamlets estimated it would cost £4m to repair, money it could ill afford at a time when £500m was required to repair and upgrade its housing stock as a whole. It was argued also that Keeling House’s two-bed maisonettes were unsuited to current local housing needs as larger families, single-parent families and the elderly came to predominate on waiting lists. The Council, desperate to get the building off its hands, was willing to sell the block to a housing association – the Peabody Trust could have had it for £1 – but none would take it on without the promise of very substantial central government or Lottery funding. In October 1993, Tower Hamlets voted to demolish the building.

Defenders of Lasdun’s vision and design rallied to save it and in the following month it was listed by Heritage Secretary, Peter Brooke. He described it as an ‘architecturally outstanding example of 1950s public housing’. It was the first tower block to be listed. Tower Hamlets, spending £80,000 a year on security for the empty block, was horrified by the decision – it couldn’t ‘afford to maintain an architectural mausoleum for the benefit of the DoE’, a spokesman said. (8)

Looking back, I’m not sure there are any villains of the piece here. Defenders of Keeling House pointed plausibly to a history of neglect and to that repair job back in 1984 now generally conceded to have been ‘bodged’. They argued that structurally the building was sound – most problems related to external panels – and that repair was a more economical option than demolition and building anew.

But the dire financial straits and circumscribed choices of the local authority were real too – as real as they had been in 1932. Critically, what did the residents of Keeling House think? The Council claimed 75 per cent wanted to move, unsurprisingly perhaps given its then parlous state. Some, certainly, were critical but many loved the building: (9)

It was so peaceful. Beautiful at night and you didn’t have to draw your curtains. There was a very good atmosphere and we had lovely neighbours: a Jewish lady used to make us lokshen soup and latkes.

As the notices to move arrived, some residents marched in protest to the Council’s Neighbourhood Offices; one was moved to poetry: (10)

When the councillors are tucked up in bed so cosy and meek,Will they think of our families they are throwing on the street.Furniture in storage, bed and breakfast for our home.You know about the crumbling block but now the time has comeWhere all the neighbours will unite and try to make a stand.We have feelings too but you just don’t understand.What can we tell our children when they come knocking at the door?Is this the sort of people our ancestors fought for?HELP US STAND TOGETHEROne tenant told Lasdun that ‘we loved living in our crumbling tower block’. Pam Haluwa of the Residents Association stated simply, ‘if you want to bring Keeling House up to a nice liveable state, we’ll all move in tomorrow’. (11) Lasdun thought it had been a ‘happy building’ and perhaps, in general, he was right. In the end, the Council were forced to put the block on the open market and it was purchased by Lincoln Holdings for £1.3m in 1999.

A £4m refurbishment, masterminded by the architectural firm Munkenbeck + Marshall followed. The spalling concrete was given a new protective coating, the flats were modernised internally and a new entrance foyer – with concierge – and landscaping were built at the front of the building.

More radically, eight top-floor maisonettes have been converted into luxury penthouses with the addition of a roof-top sunroom. The disused water tank standing at the very top of the building will be converted to a maisonette this year.

As might be expected, Lasdun, who died in 2001, was grateful that his building survived and approved the details of its redesign which won a RIBA award in the following year. But he lamented, as we should, that housing built for the ordinary people of Bethnal Green has been lost to the private sector.

Back in 2000, the new flats went on sale at prices ranging from £145,000 for a one-bedroom home to £375,000 for one of the three-floor penthouses. A two-bed flat is currently on sale for just over £500,000. But they don’t stay on the market for long. I was told that 30 of the 67 flats are currently occupied by architects and it’s a much sought-after building in a rapidly gentrifying East End.

‘In the socially committed post-war generation, a lot more thought was put into social housing than into most accommodation in the private sector’. (9) In our modern world, the market rules.

Sources

(1) T.F.T. Baker (Editor), Victoria County History, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998)

(2) Quoted in ‘Housing at Bethnal Green’, East London Advertiser, after 12 October 1932

(3) Details on Sulkin House, listed Grade II in 1998, can be found on the English Heritage website.

(4) Municipal Review, January 1954

(5) Quoted in John R Gold, The Practice of Modernism: Modern Architects and Urban Transformation, 1954–1972 (2007)

(6) Quoted in Patrick Kelly, ‘Listing the Unloved’, Inside Housing, 19 January 1993

(7) Quoted in Martin Delgado, ‘We loved living in our crumbling tower block, say residents’, Evening Standard, 30 April 1993

8) Quoted in Lee Servis, “Keeling Over!’, East London Advertiser, 9 November 1995

(9) Quoted in David Robinson, ‘The Tower block is back, but this time as a des res’, Daily Express, 22 July 2000

(10) Quoted in East London Advertiser, 23 October 1992

(11) Quoted in Robinson and Delgado respectively

(12) Elain Harwood, English Heritage, quoted in Jane Hughes, ‘Born again: the high-rise slum ‘, The Times, July 1 2000

The 1959 photographs are taken from Brian Heron, Disused Water Tank, Keeling House, Heritage Statement, December 2010.

I’m grateful also to the helpful staff of the Tower Hamlets Local History Library for their help in accessing its excellent resources.

With thanks to Municipal Dreams for this article - the original can be found HERE